Articles

Through the Eye of a Needle

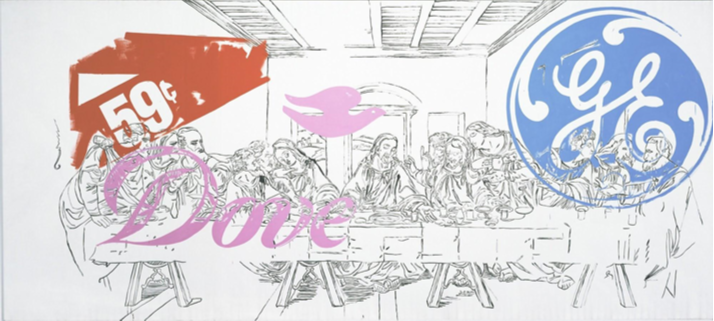

From The Last Supper, Andy Warhol (1986)

Andy Warhol’s final completed commission was a series of over 60 variations on Leonardo da Vinci’s famous The Last Supper (1496). Warhol is best known for his pop art, which often includes commercial images, such as Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). The above variation on The Last Supper combines two of Warhol’s greatest fascinations: American commercialism and Jesus of Nazareth (Warhol was a Ruthenian Rite Catholic).

This particular variation is too deep to cover sufficiently in this space, so I want to focus on the way Warhol relates the two sets of elements in the painting: the colorful commercial images--a red “59ȼ” advertisement, two pink Dove soap logos, and a blue General Electric logo--superimposed over an austere black-and-white outline of Jesus and the apostles taking the Supper.

We are intimately familiar with both sets of elements. Da Vinci’s The Last Supper is one of the most identifiable pieces of art in the world, and it represents one of the centerpieces of Christian worship. How could we not recognize our Lord revealing to the twelve that one of them would betray Him? Likewise, how many of us would fail to recognize the logos for Dove or for GE? How often have we seen “value prices” advertised in shop windows?

What shocks us is the way in which Warhol combines these otherwise familiar elements. We do not expect to see a bubblegum pink Dove logo hovering over the Lord’s right shoulder. But that is precisely the point. By shocking us in this way, Warhol is opening our eyes, that “seeing, we may perceive.”

The piece’s commercial elements do two important things: they obscure Jesus and the apostles, and they distract from Jesus and the apostles. They do both of these jobs so well that Warhol challenges us to identify the piece’s true subject. Is this a depiction of the Last Supper, like da Vinci’s original, focused on Jesus of Nazareth sharing the Passover seder with his apostles? Or is it about something commercial, essentially an ad for Dove soap or for General Electric? By making us ask these questions inside of the artwork, Warhol invites us to take them outside of the artwork and into our own lives.

Brands and their advertisements dominate modern life. This is what one means by “commercialism” in the cultural sense: that we live and experience the world predominantly in terms of profit-making mechanisms, such as brands, logos, and ads. Answering simple questions like “What shall we have for supper?” inevitably involves a parade of brand names, whether we choose to eat out at Chick-fil-A or McDonalds or to stay in and pull out some Johnsonville brats or DairyPure milk from the Frigidaire. Brands, logos, and ads are so ubiquitous that we don’t even bat an eye at them. We hardly notice them--and the incredible worldly wealth they represent.

Jesus exclaimed after the sullen departure of the rich young ruler, “How difficult it is for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God! For it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.” Our wealth, like the logos in Warhol’s The Last Supper, distracts us from the Lord and from the inspired teachings of the apostles. It obscures what ought to be clear and plain to us about God and the life eternal.

Branding is merely repackaged materialism. It is the lust of the eyes, the lust of the flesh, and the pride of life wrapped in cellophane. And it depends entirely on you thinking of your life in material terms: what shall I eat? what shall I drink?

what shall I wear? Your life consists of more than these things. Turn your attention instead to Jesus and what the Supper teaches us. He gave His body and blood for us, so we ought to lay down our lives for the brothers.

May God always rouse us when we sleepwalk into idolatry.